On average, more than 5,000 new tweets flood Twitter every second, and that volume increases when something newsworthy happens like a disaster.

Though Twitter can be a way to share information during an emergency, users can also spread rumors and inaccuracies, and a new study takes a deeper look at how false information can circulate on the social media site

Researchers from the State University of New York at Buffalo looked at tweets pertaining to two major U.S. disasters — Hurricane Sandy in 2012 and the Boston Marathon bombings in 2013 — and focused on two rumors from each event that spread via Twitter.

Looking at more than 20,000 tweets from both of those situations, researchers parsed out three types of behavior: Twitter users could either spread that misinformation by retweeting or liking the inaccurate tweets; they could try to confirm the info, most commonly by asking if the tweet was correct; or they could express doubt, saying online that the original tweet was wrong.

“We only studied people who did engage with the false information spreading, and found that about 90 percent of them just retweet it, spreading the misinformation without any confirmation or questioning,” said lead study author Jun Zhuang.

But that’s not all. The researchers then looked at what these Twitter users did when that false information was debunked, either by officials or by traditional media outlets.

“The majority of them did nothing. They didn’t correct the misinformation or delete their tweets,” Zhuang said. “That result is kind of striking for us.”

Less than 10 percent of those users who spread some sort of false information deleted their inaccurate tweets, and less than 20 percent of the same users clarified their initial, inaccurate tweet with a new tweet.

For the Boston marathon bombings, the rumors that were studied had to do with a scam in which an account promised donations to the victims for every tweet (eventually the account was suspended) and the inaccurate claim that an 8-year-old girl who survived the Sandy Hook shootings had been one of the victims.

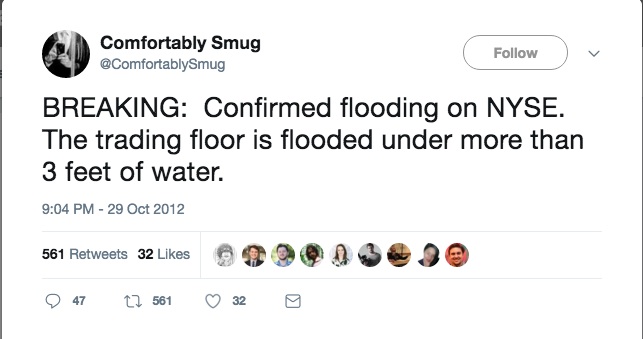

Concerning Sandy, researchers looked at the spread of the false news that the New York Stock Exchange had flooded — a report that began with one Twitter user and was eventually repeated by a TV reporter — and of a fire at the Coney Island Hospital, which was spread after a misunderstood scanner report that was actually pertaining to a car on fire in the hospital’s parking lot.

Zhuang said the study looked at these two events to see if there were any differences in how rumors spread for a natural disaster versus one that was man-made. There wasn’t, he found.

“These findings are important because they show how easily people are deceived during times when they are most vulnerable,” he said. “and the role social media platforms play in these deceptions.”

This problem is still relatively new, he notes, but he hopes that this study pushes people to be more responsible when it comes to sharing and correcting information during an emergency.

How does New York City use Twitter during emergencies?

Hurricane Sandy battered New York City when it made landfall in October of 2012, and Twitter was a main way for residents to share images of the storm’s effects as well as get much-needed information from officials. More than 20 million tweets about Sandy were sent from Oct. 27 through Nov. 1, and the city’s official channels were responsible for about 2,000 of those. Metro talked with Nancy Silvestri, press secretary for New York City Emergency Management, about how the social media site has changed the agency’s work.

What is the main role of NYC Emergency Management?

Nancy Silvestri: Our agency really serves as a coordinating agency for New York City, so we basically help to prepare the public for emergencies, coordinate emergency response and operations, and educate [the public.]

How has Twitter changed NYCEM operations?

As people have moved to social media channels, the way that they consume information and the places they get that information from has also changed. As part of our public information strategy, we felt that one of the main goals in getting people the appropriate info during an emergency is to reach people where they are. We’ve established a presence on those social media channels to reach New Yorkers where they consume their information.

But one of the things that become very apparent with social media, particularly Twitter because of its pace, is that while you can share information very quickly, you also can spread misinformation very quickly. That’s something we’ve been looking into as well for years, trying to figure out how we can make sure we can stay on top of that during emergencies in particular, because we don’t want damaging information to spread.

How did you first address false info on Twitter?

In 2011/2012, it would originally be through manual searches of Twitter — looking for hashtags people were using related to emergency situations and see if any misinformation was being spread … But we realized quickly that during an emergency, the amount of tweets that come out, the amount of energy required to do that manually was not the most efficient system. We looked around for a tool that could help us monitor social media automatically, this tool has an algorithm that searches for anything happening in New York City that might be emergency related and sends updates to users, including the city’s Public Warning Specialist.

Do you have an example of addressing misinformation via Twitter?

About a year ago in upper Manhattan, a film shoot was doing a simulated explosion. We had put out a message on our Notify NYC channels the week and day before, but not everyone saw that. A bunch of people were tweeting about an explosion in Manhattan and sharing pictures of smoke, and within 1 to 2 minutes we were able to see that those tweets were emerging on Twitter and weigh in on the conversation before it got too far ahead.

What have you noticed about New Yorkers’ Twitter habits and what do you want them to do?

Sometimes people tweet before they call 911. … One thing we’ve done across a lot of the channels is let people know that those accounts are not monitored 24/7. We want to make sure if people reach out with a really pressing thing, that they understand they might not get an immediate response if they’re tweeting at 11 at night. We tell people if they need an immediate response to call 911 or 311.