Filmmaker-actor Mathieu Amalric took his latest, “The Blue Room,” to the 52nd New York Film Festival.

Filmmaker-actor Mathieu Amalric took his latest, “The Blue Room,” to the 52nd New York Film Festival.

Credit: Getty Images

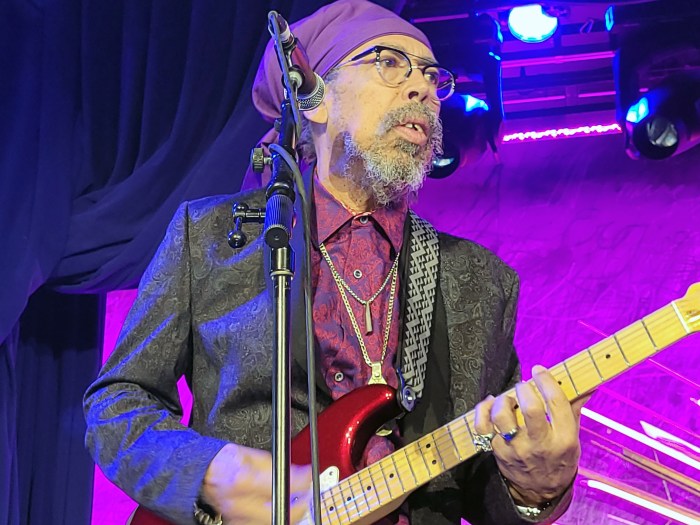

Despite one of his biggest roles — as the ailing lead in “The Diving Bell and the Butterfly” — being largely off-screen, you probably recognize Mathieu Amalric. He’s the Bond villain in “Quantum of Solace,” the oily contact in “Munich” and is a regular in the films of Arnaud Desplechin, including “Kings and Queen” and “A Christmas Tale.” But he swears acting is “the second part of my life.” He is, in his eyes, a director first.

“Desplechin invented me as an actor,” he says while promoting “The Blue Room,” his most recent directed work. “I started behind the camera before I was in front of it. I do it because of friends. I love being in their world.”

For his latest, he tackles a novel by French crime great Georges Simenon. But it doesn’t play it like a noir: It’s a fragmented memory piece which follows a man (Amalric) first in bed with his mistress (Stephanie Cleau, his real-life wife as well as his collaborator on the script), then being questioned by authorities some time later. It doesn’t let up and only gradually reveals its plot.

“It’s one of the rare novels, maybe the only one, where Simenon has no linear storytelling,” Amalric explains. “There are voices that seem to intrude during a love scene, and you understand somebody has been arrested and someone has been killed, but you don’t know who. You discover things later, but not completely.”

When he and Cleau started writing, she first extracted only the dialogue. But much of Simenon’s dialogue was also unidentified and offscreen (if you will). “We discovered there could be a battle between what’s onscreen and what’s offscreen,” he says. They then made two columns: one for each, and played with how the film would be structured.

The film came about because of the producer Paulo Bronco, who asked Amalric to do a film in three weeks. Amalric said he could do it in four. “I thought about how the RKO films were made, how b-films were produced — those Jacques Tourneur films, Fritz Lang films, Samuel Fuller. But it was mostly Tourneur,” he says, referring to the quickie, cheapie films from the 1940s, like “Cat People” and “I Walked With a Zombie. “You do it in 20 days, it’s one hour and 15 minutes, and there you go.” (Indeed, “The Blue Room” is only 75 minutes long.)

Real-life marrieds Stephanie Cleau and Mathieu Amalric play cheating lovers in “The Blue Room.”

Real-life marrieds Stephanie Cleau and Mathieu Amalric play cheating lovers in “The Blue Room.”

Credit: IFC Filmsd B

He also drew on the late filmmaker Alain Resnais, for whom Amalric twice acted (in “Wild Grass” and “You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet”). His work was key for the memory parts, notably “Je T’Aime, Je T’Aime,” his 1967 exploration of a man experiencing nothing but random flashbacks. “What’s great with Resnais is he gives you such liberty,” he explains. “You’re allowed to do lots of things in filmmaking — that’s what you think when you see a Resnais film.

He also took some visual inspiration from Simenon’s words. “The sentences made me think of still shots. Something about it made me think of cuts, which had nothing to do with the camera caressing bodies but would be more like something that would stay in the eye — like when you look at the sun too long and you have a piece of light that stays in your eye,” Amalric explains. He cites one such image as the repeated one of Cleau’s character closing her legs, which he compares to Gustave Courbet’s controversial painting “The Origin of the World,” where you see a woman’s naughty bits. “I think [his character] just doesn’t come back from that. It’s honest about how every day we have to deal with our compulsions.”

The film also deals with his character having to explain his actions to grilling detectives, which might not make sense and may even incriminate him. “Having to put words on things is difficult,” he says. “Society needs words on things, because if you don’t have a name on the thing it might be contagious. Society would prefer that people do things for a specific reason. But it’s not true.”

But briefly back to acting, one reason he does it is to see how other filmmakers work. That’s one reason he had a small role in Wes Anderson’s “The Grand Budapest Hotel.” “I did that just to see him work. It’s fascinating. He’s meticulous in his preparation, but during the shooting he doesn’t stop the camera between takes. So there’s a sort of savage spirit that enters into those meticulous frames,” he says.

“That’s why there’s this incredibly energy, this ping-pong, this speed. The camera doesn’t stop and you do it 20 times in a row. The way he gets that energy between actors is he doesn’t stop between takes. It’s fascinating.”

Follow Matt Prigge on Twitter @mattprigge