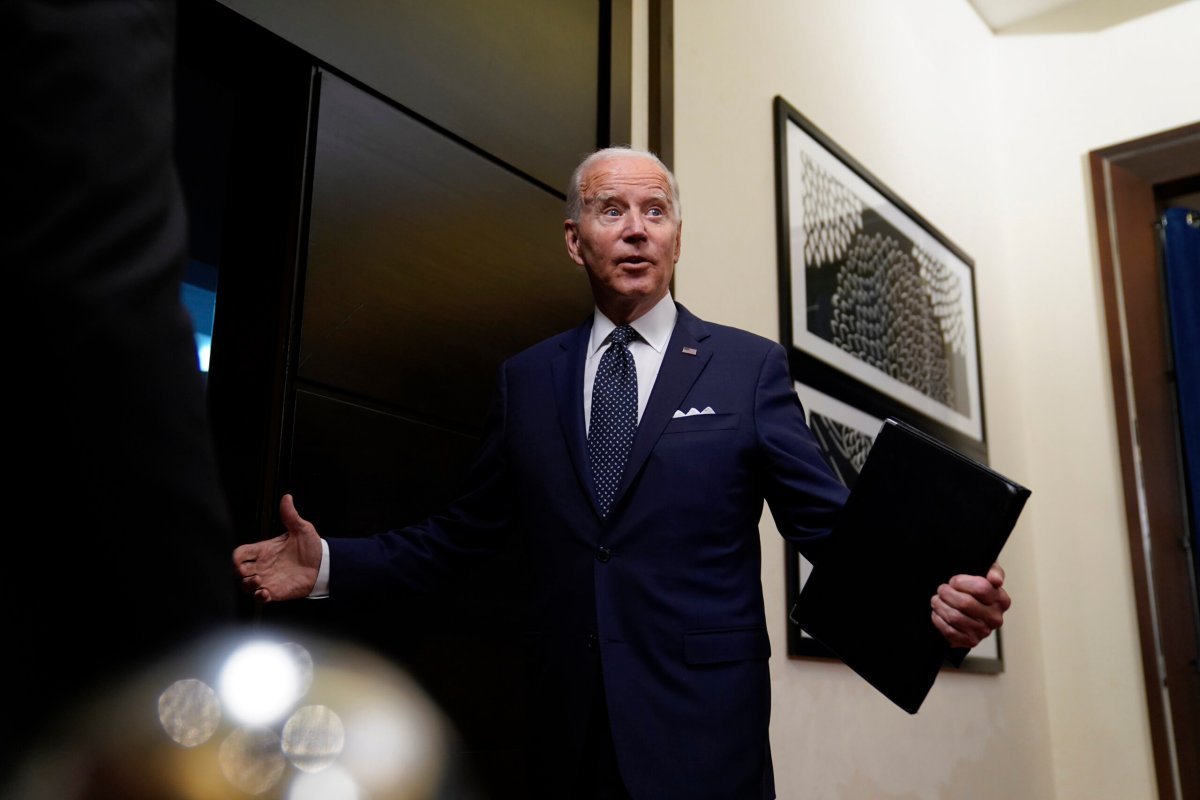

WASHINGTON (AP) — President Joe Biden seemed to bow Friday to Sen. Joe Manchin’s demand for a slimmed-down economic package, telling Democrats to quickly push the election-year measure through Congress so families could “sleep easier” and enjoy the health care savings it proposes.

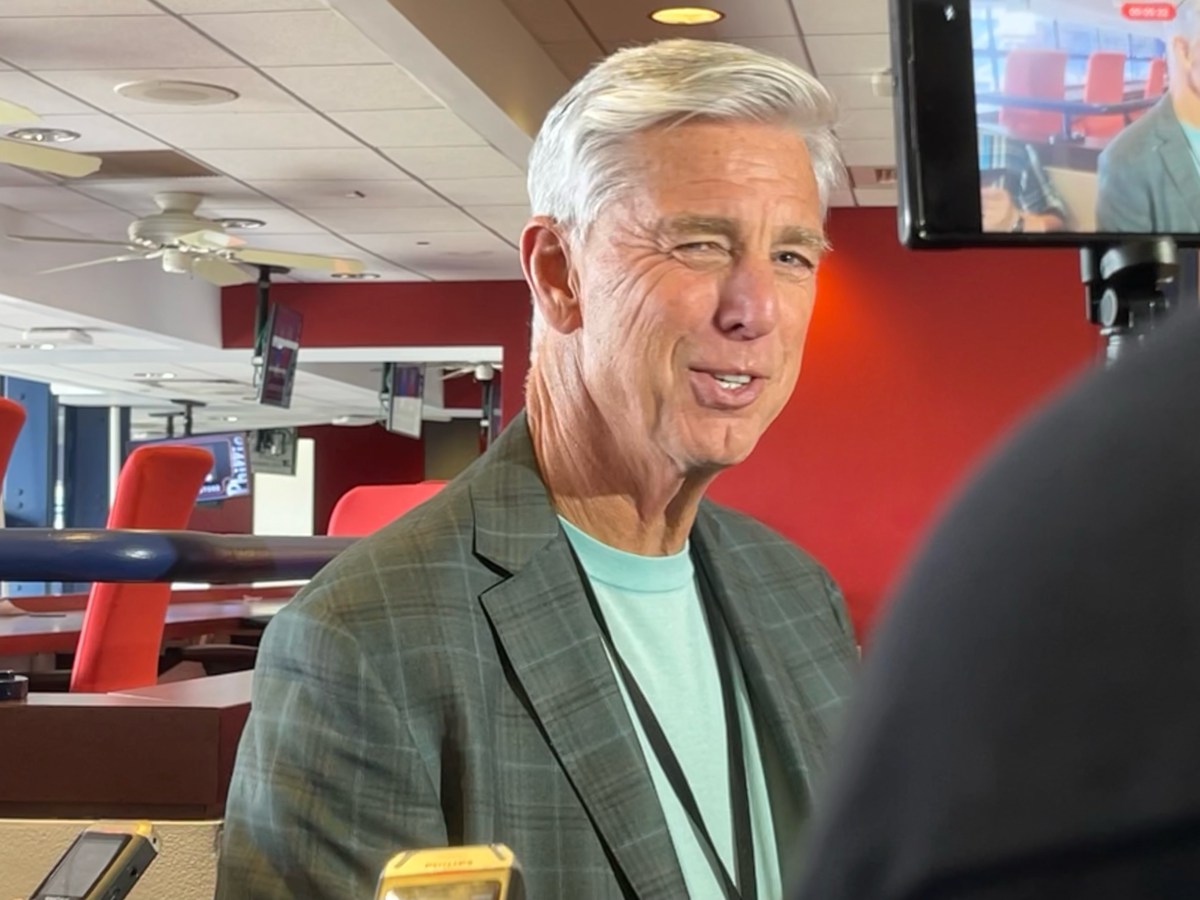

Biden’s statement came hours after Manchin, the West Virginian who is one of Congress’ more conservative Democrats, said that if party leaders wanted to pass a measure before next month’s recess, it should be limited to provisions curbing prescription drug prices, extending subsidies for people buying health insurance and reducing the federal deficit.

Even so, Biden’s directive would mean postponing congressional action on easing climate change and raising taxes on higher earners and large companies, components he and Democrats have long wanted in the economic package. That would represent a jarring setback for goals that rank among the party’s most deeply held aspirations and would delay a risky showdown over the plan until the cusp of November’s elections.

The president’s remarks underscored a growing sentiment among Democrats that after months of bargaining with Manchin that only made the president’s top-tier domestic priority ever smaller, it was time to declare victory. Reducing pharmaceutical costs, helping consumers purchase health coverage and trimming federal red ink are Democratic priorities and passage would let them flash achievements before voters that Republicans are on track to solidly oppose.

“Families all over the nation will sleep easier if Congress takes this action. The Senate should move forward, pass it before the August recess, and get it to my desk so I can sign it,” Biden said in a statement released by the White House.

He thanked Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., who has spent months negotiating with Manchin, for “his dogged and determined effort to produce the strongest possible bill” and “even offering significant compromises to try to reach an agreement.”

That seemed like an unspoken dig at Manchin, whom Biden’s statement did not mention and who in December sunk a much broader, $2 trillion, 10-year version of the package.

Though its final scope remained unclear, a slimmed-down measure contoured to Manchin’s latest demands could generate around $288 billion in savings over 10 years by letting Medicare negotiate prices for the pharmaceuticals it buys, requiring rebates from drug makers if price increases exceed inflation and other cost reductions. It would spend just a fraction of that on health insurance subsidies that expire in January, with the rest going to deficit reduction, according to early estimates.

In a sign of movement, Democrats planned to begin vetting the prescription drug language next week with the Senate parliamentarian, said a Democratic aide, to make sure there are no provisions that violate the chamber’s rules and must be dropped. The aide was not authorized to discuss the plans publicly and spoke on condition of anonymity.

Manchin, whose vote is necessary for Democrats to succeed in the 50-50 Senate, had also said Friday that if party leaders want to pursue a broader measure aimed at global warming and raising taxes on the wealthy and corporations, they should wait until later this summer. He argued that would allow time to see what happens to inflation and interest rates this month.

“Let’s wait until that comes out so we know we’re going down the path that won’t be inflammatory to add more to inflation,” Manchin said on “Talkline,” a West Virginia talk radio show hosted by Hoppy Kercheval.

After months of citing inflation fears among his reasons for seeking to trim Biden’s overall package, Manchin raised sharpened concerns this week after the government said annual inflation hit 9.1% in June, the heftiest increase in 41 years. Polls show inflation is voters’ top concern as November elections approach in which Republicans could well win control of the House and Senate.

In his statement, Biden said action on climate and clean energy “remains more urgent than ever” but acknowledged a willingness to accept delays in congressional action.

“If the Senate will not move to tackle the climate crisis and strengthen our domestic clean energy industry, I will take strong executive action to meet this moment,” he said.

Biden’s options for executive action or Environmental Protection Agency regulations could include rejecting permits for oil and gas drilling on federal lands and waters, tightening pollution allowed from coal-fired plants and restricting natural gas pipelines.

Biden’s comments marked the latest retreat he and congressional Democratic leaders have made since initially pushing wider-ranging goals early last year that would have cost $3.5 trillion or more.

Those priorities would have also provided free pre-kindergarten, low-cost child care, paid family leave and more. They ultimately fell victim to Democrats’ slender majorities in Congress and changes in the political and economic climate that have seen voters’ concerns over the inflation and the economy intensify.

Any plan that emerges faces certain unanimous opposition from Republicans, who argue its boosts in spending and taxes would further inflame inflation.

Manchin had told Schumer on Thursday that he could not support a bill now that would include other party goals like battling climate change and raising taxes on the wealthy and large corporations, according to a Democrat briefed on those talks.

The two lawmakers have been negotiating over a package that had been expected to reach around $1 trillion over 10 years, with about half used to reduce federal deficits.

Manchin said he considered his talks with Schumer “still going.” Yet his latest stance provoked a mixture of anger and pragmatism from fellow Democrats.

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., told reporters she was unsure what remained in her party’s proposal but added, “I would be very, of course, disappointed if the whole saving the planet is out of the bill.” A spokesperson for Schumer did not return requests for comment.

Rep. Pramila Jayapal, D-Wash., who leads the Congressional Progressive Caucus, said she was skeptical about Manchin’s acceptance of a health care-focused package. “Look, the guy has changed his mind” before, Jayapal told reporters. “So let’s see. I have no confidence.”

“If there was a guarantee that we could get the bigger deal in September, I’m open to that,” said Rep. Richard Neal, D-Mass., who chairs the tax-writing Ways and Means Committee. “But to go to the altar, at some point we need to say, ‘I do.’”

Delaying action until after the August break would leave Democrats facing a dangerously ticking clock. Special budget powers expire Oct. 1 that would let them push the legislation through the 50-50 Senate over solid GOP opposition, with Vice President Kamala Harris’ tie-breaking vote.

That would pose a risk that any Democratic absences because of COVID-19 or other reasons would leave them lacking the votes they need. It would also push congressional action until just weeks before the November elections, when any votes can be quickly spun into a damaging campaign attack ad.

Manchin said he was concerned that raising corporate taxes would prompt layoffs and some of his party’s environmental proposals would hinder “what this country needs to run the economic engine.”

Other Democrats say the broader measure’s initiatives would be more than paid for by making high earners and large corporations pay the costs. And they’ve noted that deficit reduction helps control inflation by reducing the government’s need for borrowing, which would otherwise help boost interest rates.

AP reporters Farnoush Amiri, Matthew Daly and Will Weissert contributed to this report.