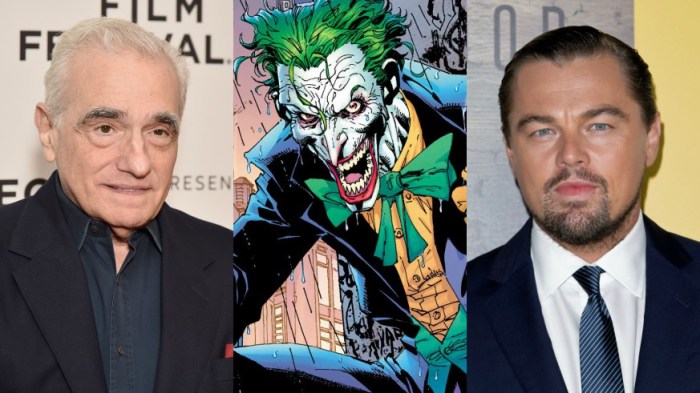

The Film Foundation and its Founder and Chair Martin Scorsese have announced Portraits Of America: Democracy On Film, their brand new curriculum for The Story Of Movies, which they insist is key in this “time of division, conflict and anger.”

Launched back in 1990 to protect and preserve motion picture history, especially because the poor treatment of celluloid now means that 90% of silent films and 50% of films before 1950 are gone, The Film Foundation started its educational program The Story Of Movies in 2000.

At the launch of Portraits Of America: Democracy On Film last week, Martin Scorsese told me and a group of other journalists that the curriculum now “seems more important than ever.” Not just because of the political landscape, but because the sheer volume of moving images circulating today means they are “unavoidable.”

“Back [in 2000] moving images were still primarily seen on movie screens, television screens, monitors, and maybe on a big billboard somewhere. Today the images are absolutely everywhere. They are unavoidable.”

“We all need to make sense of what we are seeing. For the younger people, born into this world, it is crucial that they get guided and and learn the differences between art and pure commerce.”

“We already teach our students to be critical thinkers,” Scorsese continued. “But now we must teach them to be critical viewers as well. In the end for me it is about literacy. There should be no difference between verbal and visual literacy. They are one and the same.”

Scorsese, who has overseen some of the greatest films in American history, from “Raging Bull” to “Goodfellas” to “Mean Streets,” then reflected on why our interpretation of movies is so important.

“Movies have been with us for just over 100 years now. And very quickly they became a key part of our culture, because they actually reflect back upon the culture that they come out of.”

“Moving images are records of the moments in time in which they were made and the culture they come from. As the great film critic Many Farber once said, ‘Any movie captures and transmits the DNA of its time.”

It was at this point that Scorsese touched upon how the Western genre paralleled Manifest Destiny to the US’ cultural and financial expansion in the Interwar period and how directors in the 1950s used the sci-fi genre to reflect the paranoia of the Cold War era. “It wasn’t a lecture,” Scorsese insisted. “It was a sense of what we were living in.”

This brought Scorsese to the here and now. “We are here today to introduce a brand new curriculum that explores our most cherished idea, and that’s democracy.”

“At a time of division, conflict, anger, which seems to be defining this particular moment in our culture, we felt it was so important to create a curriculum that they could study which was built around movies that span the history of American cinema and look at the struggles and violent disagreements and the tragedies of our history.”

“Not to mention the hypocrisies and false promises. These things also have to embody the best of America. The greatest hopes and the ideals of America.”

Scorsese admitted that he learnt “a lot about citizenship and American ideals” from the films he saw, specifically mentioning “The Grapes Of Wrath’s” “exploitation of labor in times of National emergency” and “Ace In The Hole’s” brutal depiction of how “human tragedy can be milked relentlessly by heartless news.”

One film that Scorsese insists has parallels to today is Elia Kazan’s “The Face In The Crowd,” which, he explained, “looks right into the heart of another issue that we are facing right now, the convergence of politics, mass media, and cult of personality, and the danger of that.”

Scorsese concluded his statement by detailing what he wants the curriculum to achieve, declaring, “Portraits Of Democracy: America On Film can inspire teachers and their students to go further and deeper into engagement about our history, our politics and our cinemas.”

This was a view shared by the other members of The Film Foundation in attendance. Film scholar Jeanine Basinger also gave an impassioned speech where she decreed the importance of making sure that young viewers understand what they are watching.

“Learning is hard. Unlearning is even harder,” she explained. “We have to think about this. We are passed the point of thinking that film studies is new. Or optional. Or something that we can generously decide to contribute.”

“The need for teaching about film in the middle school or the high school and doing it well is absolutely imperative. We are living in a world of moving images. We all know that. The need for quality classes, standards of study, goals and usage, selection of appropriate materials for serious purposes. This is all necessary.”

“Young people of America are simply not educated if they cannot understand how to see moving images. How to interpret them. How to unlock their subtext and messages. How to read them for an understanding of the country they live in, warts and all.”

“Students can be the ones to make change. Not just through films, but they can actually go out and do it. The moving image is key to the future, because outside the classroom the moving image is the major form of communication for these people. A major source of their learning. Educators have to talk to their young people in the way that they are talking to each other.”

Catherine Gourley, who is the Curriculum Author of The Story Of Movies, also detailed how to make younger viewers more visually literate.

“We want to teach students how to read a film on multiple levels. The first is simple: what is the story? What does it mean?”

“But the second is to read a film as art. A work of art. That includes the filmmaker’s use of cinematic devices. The use of film language. And the director’s vision.”

“Equally important is learning to read the film as an historically and cultural document. Asking why did this filmmaker make this film at this time and what does that tell us about society then. And what does it tell us now. That takes kids to much deeper thinking.”

You can learn more about the free education curriculum The Story Of Movies, which has taught over 10 million students to date, by visiting storyofmovies.org and film-foundation.org.