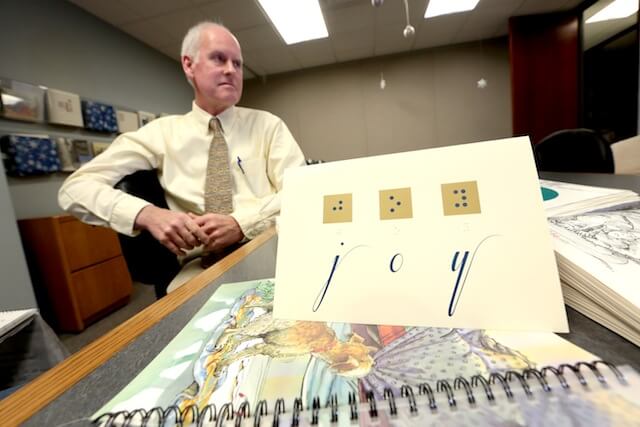

Most of us enjoy the gift of sight, an inexplicable and often underappreciated sense that allows us to take in the sparkling beauty of winter in Boston. It also allows our eyes to pour over beautiful literature, and the warmly written words of our loved ones. But for those who are blind or sight impaired, something as simple as reading a holiday card would be impossible without the art of braille. For the first time ever, the National Braille Press this year released a holiday card written both in printed English and in braille. The goal, they said, was to allow those with and without sight to share the simple but elegant message of “Joy.” Three gold boxes appear horizontally across a cream-colored background, each containing deep blue dots, in “simbraille” – or simulated braille – that spell “Joy.” The same three letters in embossed braille appear directly below each box. Across the bottom half, the word “Joy” appears in a graceful, scripted blue font. Inside the card, in print and braille, is the message: “Best wishes for a joyous season and a very happy new year.”

“We’ve done a braille Valentine for a long time, and it’s a great kind of public awareness tool,” said Kimberly Ballard, Vice President of Marketing for the NPB .

The card is just one example of how the historic press has stayed ahead of the game in its advocating of braille literacy. But it may come as no surprise that braille printing is no easy business.

“It’s expensive. It takes a lot of time. We can continue on and stay one of the leaders because our quality control is the highest in the country. Maybe the world,” said NBP president Brian MacDonald. The Boston-based non-profit is the only publisher of original braille works in the United States. For 90 years, the press has continued the tradition of supporting a lifetime of opportunity for blind children through braille literacy, and provides an education foundation for the blind community to maintain independence and productivity in their lives. The four-story building on Saint Stephen Street was once a piano factory, but today is home to an impressive collection of museum quality braille printing technology and a tightly knit staff of employees working together to put hundreds of works of braille out each year – totaling as much as 11 million braille pages. For the NBP , the struggle of competing with technology is a unique one – while mobile phones are helping sight-impaired people access more and more information, those same users require traditional braille instruction on how to use the technology. “It is a challenge. We’re definitely wrestling with that because braille levels of kids today are declining from 40 years ago. I’m hoping that it’s leveled and that it will come back up but technology is part of that challenge,” said MacDonald. “Audio is easy. Learning braille is a skill. It’s like learning a language. It really impacts literacy. If you don’t learn those basic skills as a student, you’re illiterate.” Ballard agrees, pointing not only to the nostalgia of touching and turning real-life pages, but also the necessity of absorbing valuable knowledge about technology before iPhones are fired up.

“I think there are always going to be certain things too, just like in print, that you are going to want to have in paper braille: cookbooks, and technology books. Imagine trying to figure out how to use your phone by listening to your phone,” said Ballard. The NBP’s largest project to date has been the printing of the braille edition of the 1,600-page “New American Bible,” which was presented to Pope Benedict XVI at the Vatican in 2011. Closely behind, “The Joy of Cooking,” at 1,000 pages, and “Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire”, which clocked in at more than 700 printed pages. Their next big project? It’s a secret. But MacDonald hinted that it may come tucked between glossy pages.

“We are waiting to hear about a bid on an insert in a magazine. It would be 5 million copies,” he said. “It would be a really great project if we got it. I don’t think there has ever been a braille insert in a major magazine before.”

National Braille Press love of words still transcending senses after 90 years