Years of fighting losing battles have left the NCAA almost helpless to defend itself.

The legal pile-on against the largest governing body for college sports in the United States continued Wednesday when attorneys general from Tennessee and Virginia filed an antitrust lawsuit that seeks to throw out the few rules the NCAA has to regulate how athletes can be compensated for name, image and likeness.

That pushes the number of antitrust lawsuits the NCAA is actively defending to at least five.

Denial and previous court losses — most notably a unanimous decision against the NCAA from the Supreme Court in 2021 — have flung the doors open to legal scrutiny the NCAA and so-called collegiate sports model cannot withstand.

“The NCAA and (schools) that make up the NCAA have continuously been completely stubborn,” Florida-based sports attorney Darren Heitner said. “They have resisted change. They understand that there’s been an absolute misclassification of athletes as, quote unquote, student-athletes as opposed to employees, and they’ve continuously placed very, very stringent restrictions on the capacity for athletes to capitalize and earn money.”

Three of the current lawsuits seek employment status for college athletes or are trying to direct more of the billions of dollars big-time college football and basketball to the ones who play those sports.

Amy Perko, CEO of the Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Sports, said the NCAA’s insistence of trying to govern major college football while it has no jurisdiction over its postseason and no say in how the billions in revenue it generates are spent is the root of most of the association’s problems.

“Big revenue football operates in many ways independently from the NCAA, and the NCAA serves as its legal shield,” Perko said.

The latest threats to the NCAA have originated from inside the house.

The move Wednesday by the state AGs echoed what has played out in the past two months with a multistate challenge to NCAA transfer rules.

Overall, the response from Tennessee has become typical from schools that either end up in NCAA’s enforcement crosshairs or do not receive the result they want when dealing with the beleaguered association: Attack the NCAA’s credibility. Blame it for creating an unmanageable situation. And maybe sue.

Coaches and administrators have lamented loosened transfers rules and unregulated NIL for the past two years, calling for the NCAA — which only acts upon the membership’s wishes — to rein it in.

“This legal action would exacerbate what our members themselves have frequently described as a “wild west” atmosphere, further tilting competitive imbalance among schools in neighboring states, and diminishing protections for student-athletes from potential exploitation,” the NCAA said in response to Wednesday’s lawsuit.

For a public figure, taking a stand against the NCAA is always a winning position.

“College sports wouldn’t exist without college athletes, and those students shouldn’t be left behind while everybody else involved prospers,” Tennessee attorney general Jonathan Skrmetti said. “The NCAA’s restraints on prospective students’ ability to meaningfully negotiate NIL deals violate federal antitrust law. Only Congress has the power to impose such limits.”

College sports leaders have been lobbying federal lawmakers for going on five years, since even before the NCAA lifted its ban on athletes cashing in on their fame.

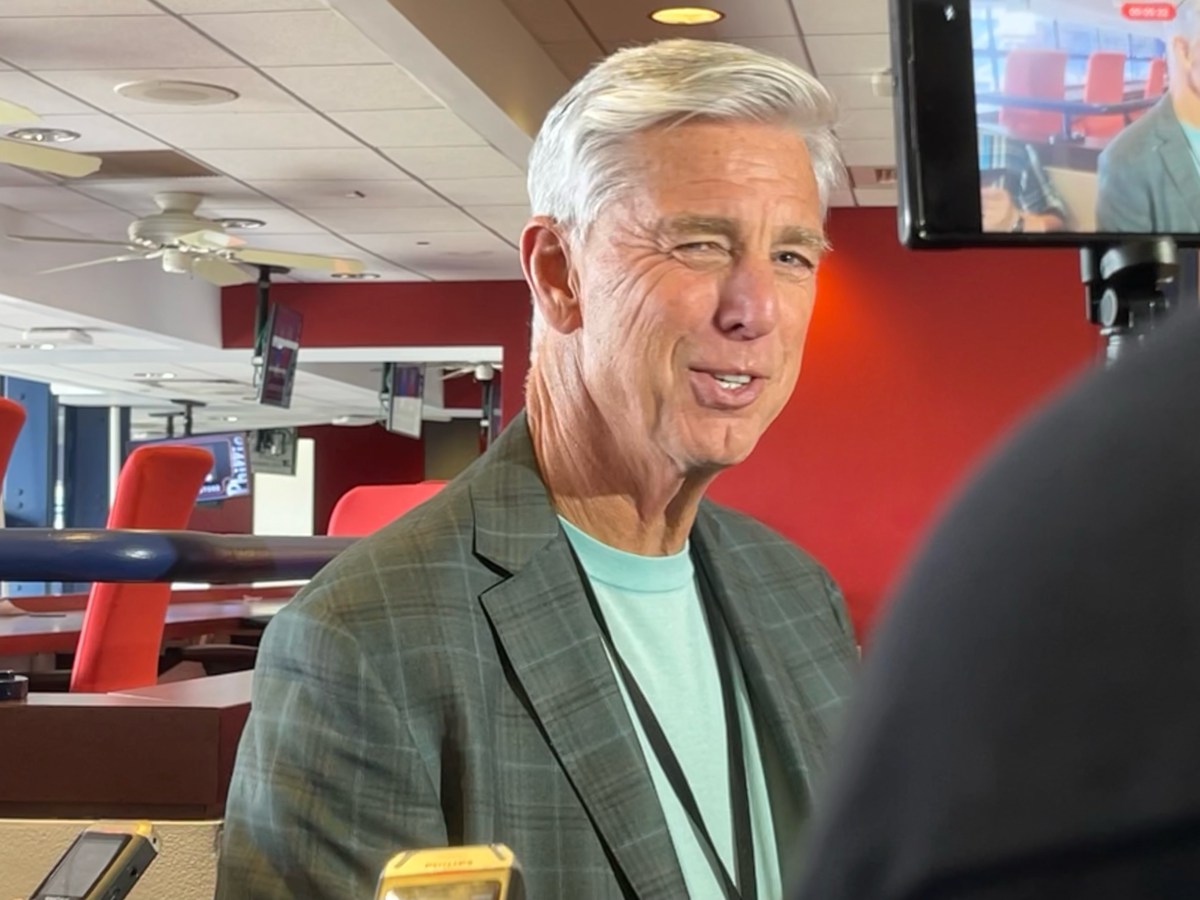

Among the biggest reasons the university presidents who sit at the top of the NCAA’s org chart hired former Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker to be its president was his political savvy.

The NCAA’s initial ask of Congress under former President Mark Emmert was for help regulating NIL. Now, that’s almost a side issue. What the NCAA needs is an antitrust exemption that will actually allow it to govern college sports without risk of being sued into oblivion.

Lawmakers have not been in a rush to help. Baker is trying to be proactive, pushing NCAA membership to make radical changes — some that could steer the big-time revenue generating sports closer to professionalism.

“Of course, we need some help from Congress to make this work,” Baker said this month at the NCAA convention in Phoenix. “The answer is: Yes, I know that, but I also believe that it’s important for us to give Congress some idea about what something might look like if they were to choose to support us.”

Mounting legal pressure leads to speculation about whether the NCAA can remain viable at all. Especially, as it risks alienating schools such as Tennessee and others in the power conferences that might be just fine without it.

“For the people who say the NCAA is destined to fail, they’re doomed. Well, it’s easy to say on the outside, but if the schools and their presidents and chancellors wish to remain part of it, and Tennessee is the only disgruntled one, let Tennessee fight the battle. We’re not getting involved,” Heitner said.

It doesn’t appear Tennessee is leading a revolution against the NCAA, but it is chipping away at an already shaky foundation.

AP college football: https://apnews.com/hub/college-football and https://apnews.com/hub/ap-top-25-college-football-poll