NOVOCHERKASSK, Russia (Reuters) – Spring in Novocherkassk, a small city in Russia’s south, is rich. Acacias bloom, the town thick with the smell of their waterfalls of flowers. White fluff flies off poplar trees in flurries, gets caught in hair, lands in soup.

Asphalt melts a little underfoot, and so that day – June 2, 1962 – when the tanks rolled in, they left their tracks imprinted in the softened street, and the blood that spilled on it seeped in and wouldn’t wash away.

That morning, Nelya, a confident 18-year-old, came over to her friend Nina, short and skinny at 16, and said: There’s a crowd on the main square. There are young men there, and soldiers. Some could be cute.

The two girls got dolled up – Nina in a white sundress and straw hat – and headed to the square. Nina Smirnova, now 75 and telling her story for the first time, recalls finding a sea of people there. Suddenly, the crowd around her surged. She fell.

At first, she wasn’t sure what happened; she barely felt the bullet hit her. “Then I looked down and felt sick. … My calf had been turned inside out, and my shoes were full of blood.”

Nelya’s gunshot wound was deeper, to the bone.

The two had wandered, unaware, into the heart of a mass protest, an almost unheard-of event for the Soviet Union. Workers from Novocherkassk’s locomotive plant, angered by a sharp cut in wages, had taken to the streets, together with their families, demanding affordable food and better pay. After a day of watching the protest grow, Soviet authorities gave the order to use force.

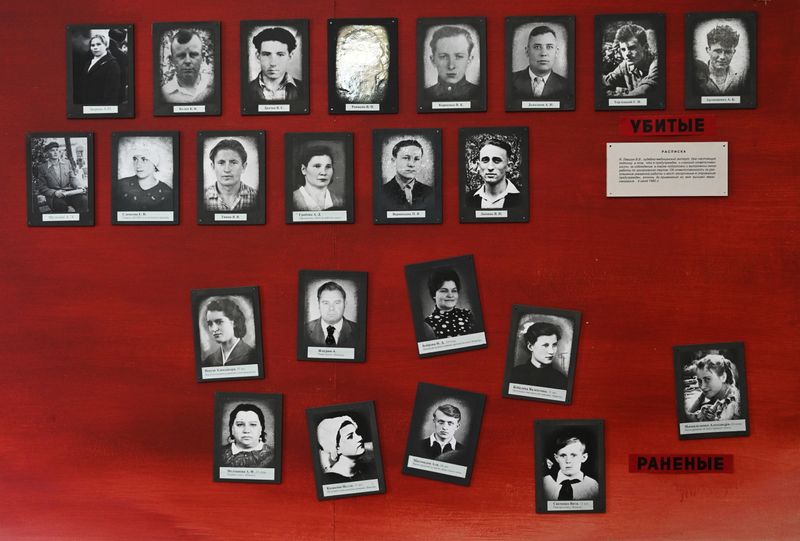

The young men in uniform whom the two girls had hoped to meet turned their guns on the crowd. At least 23 people were killed.

Now, almost 60 years later, the past continues to permeate the present for Nina Smirnova. When it comes to protests, she stays away. “And I say the same to my children, to my daughter: Where there are more than two people in a group, get well away.”

And so, for some, a lesson is passed down through the generations, not just here but across the country, following the many repressions of the Soviet era: Speaking out can carry an acutely high cost.

Despite growing dissatisfaction with economic malaise, corruption, local environmental issues and more, flare-ups of protest action routinely fail to transform into a wave that could pose an existential threat to the Kremlin. Only 16% of Russians polled by the independent Levada center in June said they would be willing to participate in a political protest.

In January and February this year, marches in support of President Vladimir Putin’s most vocal critic, Alexei Navalny, brought tens of thousands onto the streets of Moscow and St. Petersburg, with people also stepping out in around 100 other towns and cities.

But though this wave of protest marked one of the biggest challenges to Putin’s power to date, one that reverberated abroad and boosted Navalny’s already global fame, only a small minority of Russia’s 144 million citizens took to the streets.

In Novocherkassk, hardly anyone went out at all.

Reuters interviewed more than a dozen people in Novocherkassk, including three direct witnesses of the shooting and several children and grandchildren of survivors. Several described experiencing corruption, a focus of widely watched exposés filmed by Navalny. Some, too, are ready to believe that the courts are rigged, and the system stacked against them.

Still, living standards are broadly up since the start of Putin’s rule two decades ago. Able to get by, perhaps even to do better than before, many settle for stability. Moreover, the alternative carries a degree of risk.

Group protests that haven’t been authorized by the government are illegal in Russia. Thousands are routinely detained at marches in support of Navalny, and riot police – nicknamed cosmonauts for their blacked-out round helmets – have been known to use force.

Those detained can face hefty fines and jail time. A handful of cases have led to lengthy prison sentences in recent years.

Asked at a news conference last month about a recent ban on the activities of Navalny’s opposition group that labeled it an “extremist” group, Putin said that it “openly called for mass riots and tried to involve underage people in them, which is illegal.” Regarding Navalny’s imprisonment, Putin said he had broken Russian law by violating terms of his probation while abroad.

Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov declined to comment about actions taken by the authorities with regards Navalny, his organization and their calls for protests, as well as whether or not Russians have any reason to fear expressing political dissent.

In the past, Peskov has said that some participants of Navalny protests are “hooligans and provocateurs” to whom “the law should be applied with the utmost severity.” He also has said that complaints of police brutality should be investigated. The Kremlin previously has accused specialists at the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency of working with Navalny, something he denies.

On April 20, ahead of another day of nationwide action called by Navalny’s team in the wake of an attempt on his life and subsequent imprisonment, police in Novocherkassk searched for local activist Mikhail Nesvat, 23, often a one-man picketer in the town.

“They’ve gone to drive around the side streets looking for you,” a neighbor told Nesvat on a WhatsApp voice-note from that day.

The aim, Nesvat said, was to make him sign a document confirming that he had been informed about the legal consequences of “conducting extremist activities” during the protests planned for April 21. It was a warning, and police made such house calls to multiple activists across the country in the days ahead of the march.

Nesvat signed the document, seen by Reuters, adding that he didn’t mind doing so, because he doesn’t believe he engages in such activities.

City police didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment.

Nesvat said he’s not afraid to continue being the town’s lone voice of dissent. He said he believed in the importance of defending civil liberties, and to express support for the growing number of political prisoners in the country.

But as he spoke, he weighed every phrase, editing his language as he went along, for fear of saying something potentially incriminating. He doesn’t protest, he stressed. He just goes out to feed the pigeons at a specific date and time.

It’s a caution Nina Smirnova understands.

En route to our interview, Smirnova said, she took some sedatives to calm her nerves. For decades, Soviet authorities covered up the fact of the 1962 shooting, and the town was forced to act as if the tragedy had never taken place, as if it bore no scars.

Fresh asphalt was rolled over the square where the blood would not wash away, historians note.

Bodies were buried in unmarked graves. “They told us to stay silent, and we did,” Smirnova said.

In the early 1990s, as the Soviet Union was being dismantled, the first press reports about the massacre began to appear. Victims’ bodies were found and reburied. Those who had been sentenced were officially rehabilitated. An annual memorial event was launched, which now sees speeches by local government officials and the city administration invites survivors for tea and discussions about how to preserve the memory of the tragedy.

Despite that, “there’s still the fear. It hasn’t gone away,” Smirnova said. She showed the scar that still deforms her leg.

She can’t stop being afraid of a knock on the door. “You’ll leave,” she said, after I thanked her for the interview. “And then they’ll come for me, for a different reason. You understand?”

“The quieter you are, the further you will go,” she said, repeating a common Russian phrase. “This has stayed with us. It is in our blood.

PROTESTS, THEN AND NOW

This year on June 2, it rained a flood. A small group gathered by a memorial rock on the town’s main square to mark the date that the protesters were gunned down in Novocherkassk.

“It is nature remembering that tragic day,” one rain-soaked speaker said. The group wrestled their umbrellas. Nina Smirnova carried a pink bouquet.

Nikolai Gorkavchenko, a member of Putin’s ruling United Russia party and head of the Novocherkassk parliament, kept to the back.

Today, Gorkavchenko, who is 48, sharply dressed and self-assured, holds one of the city’s top political jobs.

Back in 1992, though, in the hair-raising first years after the fall of the Soviet Union, he was a 19-year-old military conscript returning home on leave. He told his parents of his work as a supervisor in a military prison, with 30 men under his watch.

Hearing this, his mother disclosed that his father had spent time in prison, too. He’d been a convict in a forced labor camp for five years, sentenced for participating in the protests in Novocherkassk in 1962.

“I was stunned,” Gorkavchenko recalled. “It was colossal.” They’d kept it secret his whole life.

It was a blow, too, to think his father could have been guilty of a crime. Soon, however, Gorkavchenko said, came “joy and understanding”. Though he emphasized to Reuters that his father was no ringleader, he was proud he was there that day, among factory workers who had gone out to demonstrate for their right to eat and feed their families.

“Truly it is a horror that people, demonstrating about their problems, trying to bring to the authorities’ attention the difficult life they lived in those years, received such a response,” Gorkavchenko said, sitting in his office in the local government building. A large portrait of Putin decorated the wall above his desk.

Asked about the possible parallels between the decision to sentence his father for participating in a protest in Soviet times and the crackdown on “unsanctioned” protesters today by the government that he represents, Gorkavchenko did not draw a line to connect the two. He said each case must be considered individually, and that protests were also put down in Western European countries without the same backlash.

Back then, there was good reason for a strike. “There really were people who didn’t have enough to eat.” It was a “survival instinct.” He would have joined in, too, for his family’s sake.

Many Russians have felt an economic squeeze in recent years. Real incomes have fallen steadily since 2013 and hit their lowest in a decade this year, following the COVID-19 crisis, according to the Bank of Finland’s Institute for Emerging Economies, which analyzes Russia’s economic development. Food prices are rising. Around 12% of Russians live below the official poverty line.

In Novocherkassk, most factories that provided employment in Soviet times have closed, residents said. Well-paid jobs are in short supply, found mostly either in the army, or at the locomotive plant where the 1962 strike began.

But, fortunately for Putin, whose arrival in office in 1999 coincided with a boom in oil prices, many take a longer view. They compare the relative calm and comforts of today with the suffering of the immediate post-Soviet period.

Returning to Novocherkassk after military service in 1992, people were on food stamps, Gorkavchenko recalled. Now, difficult as things are, people are getting by, taking mortgages, buying gadgets.

The issues raised by Navalny, questions of civil and democratic rights, ask people to consider threats that feel vague and theoretical, not the sort of thing that much affects daily life in Novocherkassk. Whereas the food shortages and wage cuts of 1962 were sharp, immediate and felt by every family in town, historians attest.

Gorkavchenko said that although Novocherkassk may have its share of problems today, there is no appetite for a strike like in 1962. He lists the supermarkets of which there is no shortage in the town. “Is there enough food? There’s enough.”

A SUMMER, AND A LIFETIME, OF FEAR

In 1990, after the fall of the Berlin Wall, a group of local activists spoke with witnesses and participants of the events of June 1962 and recorded their memories. The result is a macabre snapshot of a confused day.

A woman in the back of someone’s pickup truck, silent and wide-eyed, her knee a bloodied mess. A scattering of casings. Bodies hauled into a bus. “How will they fit with all the seats in there?” one witness recalled thinking at the time.

Nina Smirnova spent the summer of 1962 at home, hiding a leg covered in a green healing liniment.

Her parents were terrified they would be deported. “My mother was waiting for us to be loaded into wagons,” she recalled.

Nelya and hundreds of others were interrogated by secret police. Supposed ringleaders were tried in public show trials. Seven were executed. More than a hundred others were deported to prisons and labor camps.

Gorkavchenko’s father spent five years in Russia’s far north, felling trees in frozen temperatures. A talented football player, he was on the prison team.

After returning to Novocherkassk, he took a job in an electrode factory, got married and had two sons. But until the Soviet Union fell, he carried with him the burden of being a former political prisoner, never fully free, always at risk of re-arrest.

“It was this hook, driven into him … and they kept him on that hook for all those years,” Gorkavchenko said. But though he thinks that some Russians today still live under this same pressure, he believes the lesson of 1962 has been learned. Power cannot be blunt and inflexible; it must negotiate, listen and respond.

Yuri Lysenko, Novocherkassk’s top official, agreed. “The most important conclusion that we must all draw from this tragedy is that the government must hear its people,” he said at the memorial on June 2, shielding a bouquet of red flowers from the rain. “The government must address all the issues that our brothers and sisters have.”

When the Kremlin proposed raising the pension age in 2018, the Communists and other political parties considered to be in the “systemic” opposition – which critics say are approved by the Kremlin and are obliged, as a result, to keep their opposition within bounds – organized protests across the country. Some too were called by Navalny’s team.

Novocherkassk’s demonstrations, organized mainly by the Communist Party, received official sanction. Hundreds attended, signed petitions and gave their votes in a local election to a Communist candidate over Putin’s party.

Nationally, the government made some concessions but kept the pension age increase in place. The protests died down.

“I think people should and must express their views,” Gorkavchenko said, so that the government can be faced with and learn from “bitter truths.” Some protests can be good, too, he said, “if the protests are correct.”

SHIFTING ROLE OF THE COSSACKS

Russia’s south is the land of the Don Cossacks, and Novocherkassk is its historic capital. Gorkavchenko’s parents were both Cossacks, and he remembers a rural, happy childhood, replete with “singing, dancing, music, the whole village reaping hay, making bales,” he said.

Though living a more settled life in Soviet times, the Cossacks are a warrior caste, known for their horsemanship and for protecting Russia’s borders in the south, in exchange, in Tsarist times, for more autonomy.

The protest in 1962 wasn’t the city’s only instance of revolt. In 1917, after the Russian revolution brought in Soviet rule, Don Cossack fighters, defending their special status from their headquarters in Novocherkassk, launched an armed rebellion against the incoming Soviet state and proclaimed an independent Don Republic that lasted three full years.

Experiencing a state-supported revival in recent years and proclaimed symbols of Russian patriotism, some official Cossack groups have become as staunchly supportive of the Kremlin as they once were of the Tsar.

In Moscow, some Cossacks have posed an additional threat of violence to Navalny supporters. At one demonstration in 2018, Cossacks were seen beating protesters with leather whips.

But in Novocherkassk, their local leader, or ataman, Vitaliy Bobylchenko, takes a different stance.

On June 2 this year, setting aside his umbrella to lay flowers by the memorial rock on Novocherkassk’s main square, the ataman said he believes in negotiation.

When there was a small pro-Navalny protest in the regional capital, he travelled there and spoke with young demonstrators, he said. “First and foremost, we had a conversation. … We found mutual understanding.”

It is what should have happened in 1962, Bobylchenko said.

His grandfather was on Novocherkassk’s main square that day, he said. A veteran of the Second World War, he had lost both his legs and was in a wheelchair. “When the shooting started … he couldn’t run away so hid behind his chair. And he survived.”

LIFE IS “BEARABLE”

In his family home outside Novocherkassk, Nikolay Ilyin watches a lot of YouTube. There he follows Navalny’s channel, where the opposition leader posts his video investigations.

Ilyin’s wife recently bought him headphones, so he’d stop making her listen to them, too.

Many elderly people in Russia don’t go online, but Ilyin, 78, has always been good with tech. He built his town’s first electric guitar in the 1960s. He had a gang of “radio hooligans,” as he calls them. They’d make illicit radios to catch banned stations like Voice of America or the BBC.

On June 2, 1962, Ilyin was deep in a conversation about radio parts in the lobby of a cinema in central Novocherkassk when he first heard the salvos.

“Tat-tat-tat-tat. It was a bit muted, a bit far away,” said Ilyin, who was 18 at the time. He saw a crowd running down the street. The boys began to run as well.

Ilyin saw it in a flash; his friend and neighbor, 15-year-old Anatoliy Artyushenko, seemed to trip and fall.

People shouted: “A student has been killed!” It was Artyushenko. The teenager was brought into the lobby of the cinema and later died, according to an account by a local historian.

Artyushenko’s father, who has since died, later told Ilyin that, upon hearing of the shooting, he went looking for his son. He found his body under a pile of corpses in the town. He tried to bring the body home but was detained. The body was taken away, and the father was put under police detention for some time.

Artyushenko’s mother went looking for her child, too. Her brief first-person account was published in one of the first newspaper reports about the tragedy after the Soviet Union fell. There, Olga Efremovna described how she stood after the shooting in the offices of Soviet officials, demanding that they hand over her son’s body. They declined, told her she was mistaken, there had been no shooting, no one had been killed at all, and dispatched her to a psychiatric hospital, the clipping said.

Ilyin went back to work at the plant where the strike began, but after his second interrogation by secret police, he decided to move to a different town. Arriving there, however, he was told to go back home: We don’t need strikers here.

He witnessed injustices across the Soviet Union, and quit job after job, unwilling to stand for it. “I’m generally disposed in life to be opposed to all and everything,” he said.

But he doesn’t think there is an appetite for protest today. Things are still tough, and there’s a lot he’d like to change, but the situation is different. “People are surviving, bit by bit.”

“A full-blown strike, if there were one, would be a last resort, when people would either get a serious pay cut or have nothing to eat,” Ilyin said. “Otherwise, I don’t think anyone would go.”

His wife, son and younger daughter all have steady jobs at the plant where the protest began. His elder daughter, Nadezhda Lazar, 34, is a hairdresser and stylist.

Wages at the plant can go up and down, but jobs there are so desirable that employees hold on through thick and thin, Lazar said, for fear of being replaced. No one dares complain.

Plus, she said, people who have worked there for a long time have done pretty well for themselves. “They’ve built houses, bought cars.”

She’d like to start a business with her brother but is afraid to invest her savings in a project that could be snatched away at any instant. The courts and police would not be on her side, she thinks.

But she has never been to a protest, she says, doesn’t know anyone in town that has, and says she would never go. “I try not to get involved because I see that it’s totally pointless. I don’t know who is in what party, I don’t care which MP comes into power. So long as there is order.”

Normal people will never achieve any change, she says. Young supporters of Navalny will achieve only the fraying of their nerves and a police baton to the head.

This, she said, was just recently on show. The owners of stalls and shops at several large regional markets turned up to work in April to find their businesses encircled by government riot police. The markets had been ruled illegal, despite existing for decades.

The Rostov region governor ordered his deputies to find the market’s traders a new home, a press release by the regional government showed. The press service for the Rostov region government didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Lazar said that a couple she knew had invested all their wedding money in a business there. “People came out, they were complaining. … They were encircled.”

It was a lesson for everyone, she said. “People can’t do anything. … They organized a protest. In vain.”

Lazar’s approach is to work within the limits, and she advised would-be protesters to focus instead on themselves, on getting an education, maybe a second job. “You won’t earn a million even if you work 24 hours a day, but still, everyone nowadays has a car.”

The top-level corruption that Navalny’s videos purport to depict, the hypocrisies and egregious wealth, she says is nothing new.

“We’re simple citizens, we’re far away from all that,” she said. “Just make it so that people have what they need. So that education is genuinely good, so that medical care is provided in a timely fashion, so that the wages people receive allow them to go on holiday, and so on. That’s the most important thing.”

And, for now, Lazar and her father think this is being done. “It’s bearable,” her father said, sitting in a café on the corner where his friend died that one June day, poplar fluff dancing in a spring snowstorm on the street.

“It’s bearable,” Lazar agreed.

(Reporting by Polina Ivanova, editing by Kari Howard)