By Humeyra Pamuk

WASHINGTON (Reuters) – U.S. President Donald Trump has decided to step up a sanctions campaign on Venezuela’s oil sector and will be more aggressive in punishing people and companies that violate it, the top U.S. envoy to the Latin American country said on Monday.

Venezuela’s socialist President Nicolas Maduro remains in power a year after Washington recognized opposition leader Juan Guaido as the legitimate president, and has worked to push Maduro out. Maduro has retained the support of Russia and China.

The United States imposed sanctions to choke off Venezuela’s oil exports in the aftermath of Maduro’s 2018 re-election, which was widely described as fraudulent. But customers in China, India and elsewhere continued importing, so Venezuelan state-oil company PDVSA’s exports only fell by about a third.

Washington had not followed through on threats to extend the sanctions on any foreign company doing business with PDVSA – until last week, when it blacklisted Rosneft Trading, a subsidiary of Russian energy giant Rosneft, to pressure Moscow.

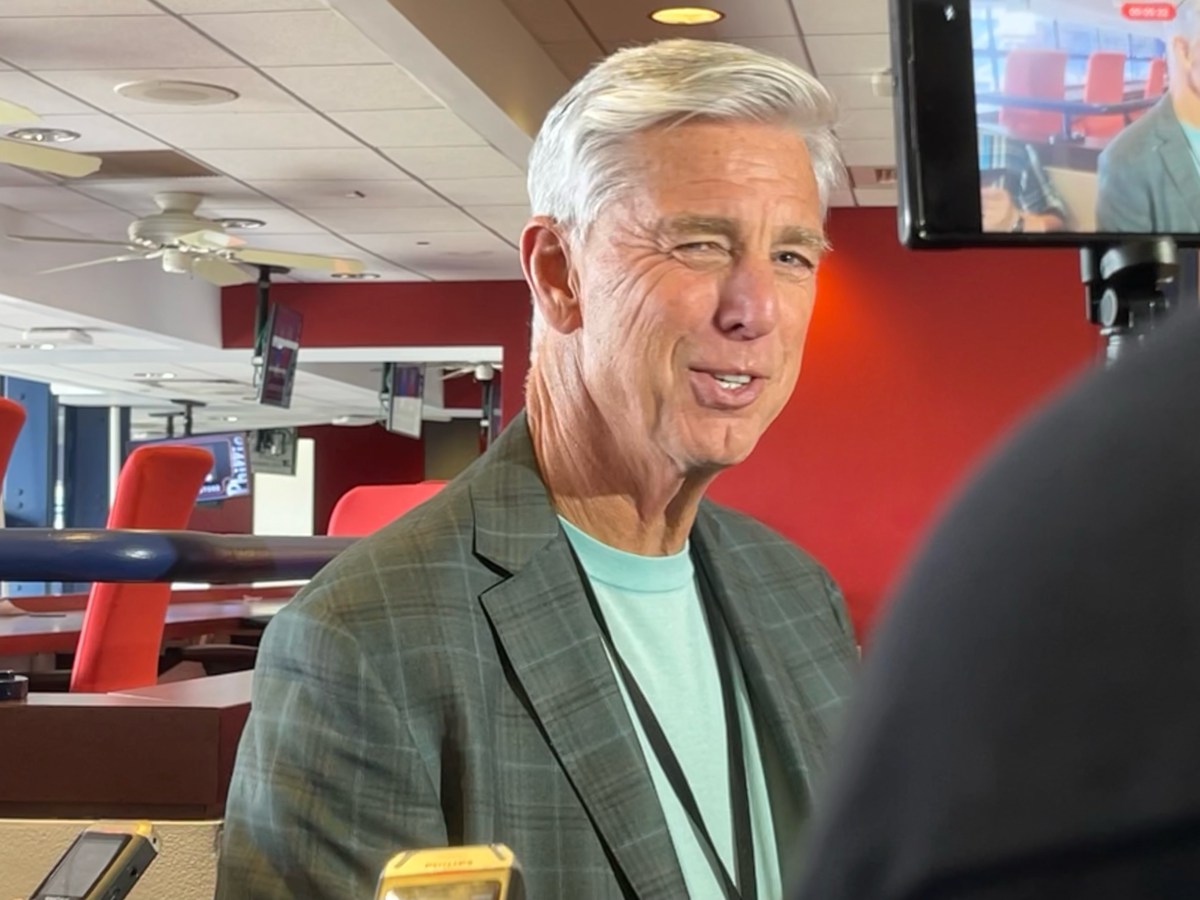

U.S. Special Representative for Venezuela Elliott Abrams told Reuters in an interview that there will be more sanctions as Washington plans to go after continued customers of Venezuelan oil, including those in Asia, and target intermediaries helping Caracas hide the origin of its oil.

“The President has made a decision to push harder on the Venezuelan oil sector and we’re going to do it. And what we’re telling people involved in this sector is that they should get out of it,” Abrams said.

Washington’s ramped up pressure campaign is not going to focus solely on Russia, Abrams said, but will also target entities throughout the supply chain.

“Rosneft Trading is a middle-man. What about the customers who are mainly in Asia? We will be talking with them. So it isn’t a Russia focused campaign, it’s focused on the critical points in the petroleum sector from production to shipping to the customers,” he said.

Venezuela’s oil exports last year plummeted 32% to 1.001 million barrels per day, according to Refinitiv Eikon data and state-run PDVSA’s reports. Rosneft was the largest receiver and intermediary with 33.5% of total exports, followed by state-run China National Petroleum Corp (CNPC) and its units with 11%.

TARGETING CUSTOMERS, STS TRANSFERS

Russia’s Rosneft became the largest intermediary for Venezuelan oil last year, when few were willing to trade it, and has shown no signs of backing off. It called U.S. sanctions imposed last week illegal and said it plans to consider options in reaction.

With Rosneft acting as an intermediary and helping solve shipping bottlenecks, PDVSA kept sending crude to China – its largest destination this year – through ship-to-ship transfers on the high seas, disguising the origin of the oil, according to Refinitiv Eikon data.

Asked if sanctions against Chinese companies purchasing transshipped Venezuelan crude were on the table, Abrams said: “Yes that is on the table.” But he said conversations advising the parties to stop would come before sanctions.

Washington was also examining ship-to-ship transfers intended to obfuscate the origin of an oil cargo, and name changes of companies involved in transactions of Venezuelan oil.

“What people do is switch from one company to another so the company that takes the oil may flip it to another company that ships the oil, flip it to another company that sells the oil. We follow all of that,” he said. “We are going to follow up with the companies that are engaged in this and we are going to sanction them.”

In January 2019, Washington recognized Guaido as Venezuela’s legitimate interim president and ratcheted up pressure on Maduro. Dozens of other countries including in Europe and Latin America also support Guaido, who was Trump’s guest at the White House in early February.

Rosneft had long claimed that its lifting of Venezuelan crude was permitted under the sanctions as it was to pay back a loan issued before the penalties. Abrams did not confirm the argument but said PDVSA was about to complete paying the debt off.

“Rosneft was owed $5 billion- 6 billion..They were paying off the whole thing, we think all debt is being closed out,” he said. “Even if that were true, it doesn’t matter.”

As of the third quarter of 2019, PDVSA owed Rosneft just $800 million. Rosneft removed the data on the debt from its 4th quarter earnings, released last week.

(Editing by Richard Valdmanis, Chris Reese and David Gregorio)