The man who makes sure the city puts its money where its mouth is has his own vision for a progressive New York City.

Comptroller Scott Stringer spent his first year in office going after city agencies that failed to live up to their financial commitments, sometimes even butting heads with Mayor Bill de Blasio on budget priorities. The two came to a head when this time last year when Stringer poked Mayor Bill de Blasioinsufficiently accounting for long-expired labor contracts, and the comptroller hasn’t been shy about calling out the mayor’s office and city agencies since. “I’m the auditor in chief. I’m the guy you don’t want to see at the party,” Stringer told Metro.

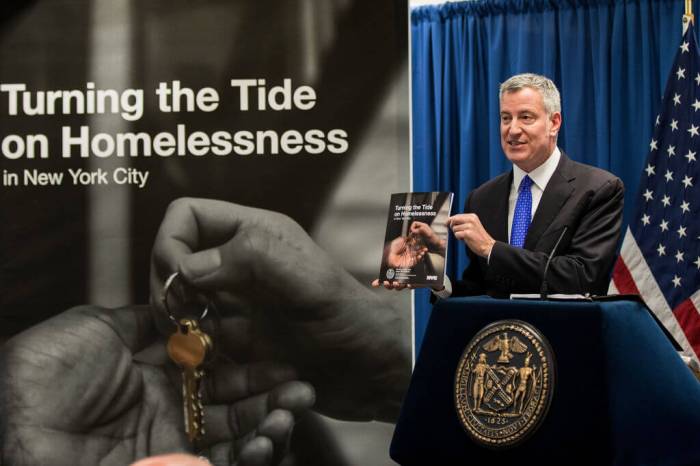

About a quarter of the city’s public workforce still needs a contract, specifically a handful of public safety unions. The Detectives Endowment Association signed off on a contract on Friday. The only union left not in active negotiations with the city is the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association, whose case is in arbitration. Stringer gave a thumbs up to the de Blasio’s progressive priorities and financial pragmatism with the mayor’s latest $77.7 billion budget introduced Monday.

“There doesn’t seem to be an overreach in spending,” he said. “At first blush, it looks to be a very responsible document.”

Stringer didn’t have strong words about de Blasio’s proposal to spend $3.2 million on hiring 40 staffers to litigate lawsuits against the city that the mayor called frivolous.

In late January, the administration came under fire for agreeing to settle a $3 million lawsuit filed by a man shot in the leg after he pleaded guilty to menacing a cop with a machete for $5,000.

Common practice by the city has been to settle these claims for negligible amounts of money compared to what it would cost to take it to court.

“We’ll spend what it takes,” the mayor said last week.

“I’m glad on the litigation side the law department and mayor are also taking a look at this,” said Stringer, whose office has been actively involved in approving both small major settlements with the city. “We raised this issue a year ago.” Repeating one of the mayor’s refrains from the last budget season, Stringer said progressivism and fiscal aren’t mutually exclusive.

“You have to be able to do both,” he said.

While the mayor and City Council dole out money to the causes and concerns targeting inequality across the city, Stringer makes sure the money goes where it’s supposed to: New Yorkers.

“We have to build an economy that continues the tradition of New York City. We need an aspirational economy,” Stringer said. “The job of City Hall is to clear the decks so the aspirational move to the middle class can happen.” How that middle class can grow is at the heart of both Stringer and de Blasio’s commitment to more affordable housing and job creation by boosting both small business and education.

“If the entrance fee to New York is a $1 or $2 million condo, then no one is going to be able to come live here or stay here,” Stringer said, applauding the de Blasio administration for its commitment to create new and affordable housing across the city. However, Stringer implored that the city work with communities to their neighborhoods on how those changes come about.

“Skylines change and they should — it’s New York. It always changes,” Stringer said. “But they have to change with the abilities of communities to have a say.”

Part of making sure his own office comes through for taxpayers is to keep agencies honest. In his first year in office, Stringer’s office zeroed in on the Department of Education’s inability to deal with overcrowded classrooms and its failure to properly track allegations of misconduct. The comptroller’s office also released scathing audits of mismanagement by the New York City Housing Authority and its inability to secure almost $700 million in savings and funding to repair the homes of the more than 630,000 New Yorkers who rely on public housing. Stringer, whose work with and criticism of the housing authority stretches back to his days as a state Assembly member, lambasted NYCHA for not keeping up with demands from its residents.

“This is where we can change income disparity,” he said. “This is where we can put an progressive agenda to work. But NYCHA leadership does not recognize the audits. They can’t admit that there’s a problem, so how can they fix it?” To fix that problem, Stringer vowed to make sure agencies follow through with the promises they make after every investigation, especially NYCHA.

“Otherwise what’s the point of doing an audit? My job is not just to blow the whistle and say gotcha,” he said. “We want to change public policy.”

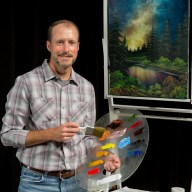

Comptroller Scott Stringer: ‘The guy you don’t want to see at the party’

Miles Dixon/Metro