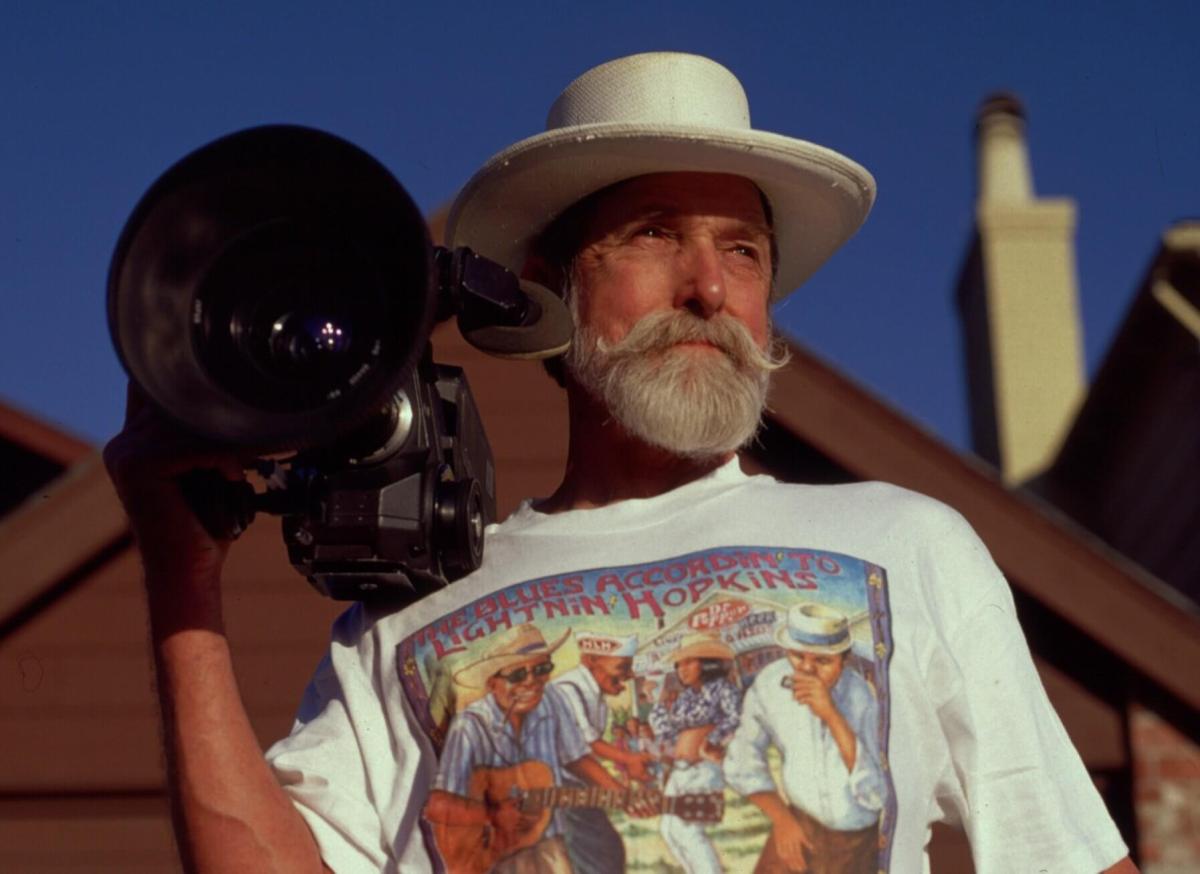

Les Blank: Always for Pleasure When asked at the 2011 Robert Flaherty Film Seminar to explain the motives behind a certain shot in his 1968 doc portrait “The Blues Accordin’ to Lightnin’ Hopkins,” Les Blank was succinct: “I shoot the stuff I like and I don’t shoot the stuff I don’t like.” It’s may seem simplistic to the point of absurdity, but it’s a truly radical approach to filmmaking. Art, we’re constantly told, is about exposing truth, especially the kind that’s grim and unpleasant. Blank only shot the stuff that makes him, and even moreso the people profiled in them, happy. Throughout his films, most of them medium-length, there’s gumbo, there’s garlic, there’s red beans and rice. There’s the blues, there’s Zydeco, there’s Polka. There’s cheap beer, including Werner Herzog nursing a bottle of Heineken. (The latter sight is in the sort-of self-explanatory “Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe,” which is not on this new Criterion set but which is on the set for Blank’s “Fitzcarraldo” doc “Burden of Dreams.”) Who does this? Almost no one but Blank filmed little but joy, much less the specific enclaves he invaded. He hung with groups on the margins, people who live outside of social norms, where people get by on little, and what little they have — usually food or music, as well as each other — tends to be the best stuff on earth. He’s no objective reporter; his camera pushes close in on seriously delicious-looking food, or gets in the middle of madcap revelry. His titles are approval signs of what he found: “Spend It All,” for Cajuns; “A Well Spent Life,” about blues guitarist Mance Lipscomb; “Always for Pleasure,” a hang at Mardi Gras; and a serious contender for best film title ever, “Garlic is as Good as Ten Mothers” — an hour-long valentine to that most pungent of vegetables, which quickly atones for one of its initial images: mushing it out through a demonic garlic presser.

The Criterion Collection

$124.95

One quick final note: Most of Blank’s films are straight-up valentines, but one is a bit more complex. Completed in 1994, “The Maestro: King of the Cowboys” seems to have found another kindred spirit: Gerald Gaxiola (yes, aka “The Maestro”) an outside artist who mimics the Impressionists but on the subject of cowboys. Like other subjects, he’s a big fish in a tiny, tiny pond, who prefers to live meagerly. Unlike them he’s also driven by the need to be bigger — or at least to sell a single painting. As a short catch-up profile on the set reveals, Gaxiola still hasn’t sold one, but even in the film he’s trying to break through, in part by pestering and even insulting star artists like Andy Warhol and Christo. You can sense Blank parting ways with him as he reveals his sour desperation, yet still wanting to give him a platform. (He even returned later for a follow-up.) It’s the one time Blank has issues with his subjects, and it sheds a critical light on his other films, suggesting they too may be more complex than they seem.

Follow Matt Prigge on Twitter @mattprigge