The documentarian Nick Broomfield is sometimes lumped in with Michael Moore because they share the same shtick of inserting themselves into their films. Not only was Broomfield doing this before Moore made “Roger & Me,” but his films — including “Heidi Fleiss: Hollywood Madam,” “Kurt & Courtney,” “Biggie & Tupac” and two films with Aileen Wuornos — tend to be about much more than him. He’s only in a little bit of his latest, “Tales of the Grim Sleeper,” which finds the soft-spoken, sometimes bumbling English filmmaker heading to South Central to examine the “Grim Sleeper,” a serial killer who ran rampant over the area for 25 years before being caught. But this becomes an excuse to get to know people in a disenfranchised and demonized part of one of America’s richest cities. What is your history with this area of the city?

I’ve lived in Los Angeles a long time. I’ve always been aware that it’s a deeply divided city, with these amazingly rich areas but where the majority is very poor and completely disenfranchised. When I read about the Grim Sleeper story, the thing that most interested me was the community. The people are completely unrepresented by the rest of the city, particularly the area that witnessed the Watts riots and the L.A. riots more recently. They call it something else; they don’t call it the “riots,” they call it “the uprising.” It’s a whole different attitude. I wanted to educate myself a bit more about the city. And I thought how is it possible — or, to put it another way, it is only possible that this is where these murders happened, what that number and over that period of time, and literally nothing was done about it. When he was caught he was caught by a computer. In a very short period of time I was bale to uncover things the police you’d think would have uncovered in a matter of weeks, if they had wanted to. It’s a part of town that seems to have been forgotten by the rest of it.

When the funding, the programs stopped in the late ’70s, the community’s communication with the rest of the city ceased. No one was coming in. I knew people who had set up medical centers and reeducation programs and tried to get people jobs and opportunities, tried to get the community going. There’s nothing now. There’s no money going into that community. This is the result. There are parts of South Central where there’s no shop, there’s nothing. The roads aren’t surfaced properly. It feels like the bomb has gone off. The restaurants are terrible. You can’t get a decent meal. What really comes across is the people. The bulk of the film is spent chatting with people, and the real star winds up being Pam, a former prostitute who leads you around the community.

The people we met were so appreciative of the fact that they were able to talk at length about their lives. I did think it was the first time it ever happened. They’re more than capable of talking about it. There was no need for me to say anything. They were incredibly articulate and very aware of their position. All these people who’ve lived in Los Angeles all their lives were warning me not to go down there, because dreadful things would happen. There is this boogeyman impression in Los Angeles. That happens if you have this whole community who are misrepresented. It becomes this non-place. It’s like the barbarians behind the wall. It was a fun film to make because the people we met were such amazing people. They felt like this was their film. They knew it was more than a 30-second spot on the local news. There’s long been this idea of South Central as a place no one should go to. Watching this, it seems like that’s in part a myth.

It is, and I never felt frightened there. I felt a lot more frightening doing other things, but I never felt frightened there. Obviously we were sort of protected by having Pam and people like Richard around with us. Actually the initial cameraman I had left after four days. He got totally freaked out. He was English, and he couldn’t do it. And then I’d never worked with my son before. He had worked a lot with Hubert Sauper, who did “Darwin’s Nightmare,” and he had come back from the Sudan. South Central is a breeze after the Sudan. As you often do, you include a lot of the nuts and bolts of your filmmaking in the film. You show yourself watching people, and there are interviews that happen through car windows, showing that you just met them for an impromptu chat. There are a lot of documentaries where someone writes a script and they go off and make that script. I always feel there’s a much more interesting film out there than anything you could ever imagine. The film should reflect that experience. It should reflect your voyage of discovery with these people. Sometimes you go through changes. Sometimes you think one thing at the beginning and think something different at the end, which is always more interesting. This was a voyage of discovery, and I wanted that to be reflected in the story of the film. It became about a community that was abandoned. It was abandoned by the police, it was abandoned by the schools, abandoned by the rest of the city. What interests me about documentary is that it can be so spontaneous. It can be something that evolves in that way. Since [D.A.] Pennebaker and [Richard] Leacock invented this camera that can be carried around, it changed our ability to tell stories in different ways. There’s no need to make the kind of quasi-fiction films in a documentary style. I’m from the opposite school of documentary filmmaking. Your first rash of films were more fly-on-the-wall, but starting with 1988’s “Driving Me Crazy” you started inserting yourself into your documentaries, almost like a host or character. What was your initial reason for doing that? The reason I did it initially was I did this film about Lily Tomlin [1986’s “Lily Tomlin”], which is not a good film and then she sued us afterwards. The best bits of the film were her abusing us during the film, treating us like we were s— and being completely neurotic and crazy. We had a lot of stories like this, but we never shot them. It would have been a great film, but we didn’t shoot that film because we were busy shooting this much more conventional film about her creating her show. If we had moved the boundaries back another step we would have not only her making the show but we would have understood this very talented but deeply neurotic artistic process she goes through before. She’s motivated more by a sense of insecurity and impending failure than what she tells everybody else. I’ve learned much more from my disasters and mistakes than from successes. I really felt we should have made a different film then. And then it became obvious while we were making “Driving Me Crazy” that the film was going seriously awry right from the beginning, when the funding fell out and the funders were fighting with the producer. I was ready to leave, but my producer said, “Surely we can make some film. There’s a bit of money left and we’re staying in the best hotel in New York. What are you going to do for three months in New York anyway?” So I did it. It was kind of an experience. I don’t like appearing in my films, but it was a new way of telling [non-fiction] stories. It was before Michael Moore. And then there was this phase of editors saying, “Try and stay out of the film a bit more if you don’t mind.” And I did, and then people wanted me to be in the films. And then it became less interesting. Because you don’t want to become a performing rat [laughs], where it’s expected of you to insert yourself in. I like this film, because I really did not want to be in it. I’m just connecting dots more than anything else. Obviously you do something like [“Sarah Palin: You Betcha”], and she won’t take part and you’re too far into production to cancel it. You know you’re on this doomed mission and that’s all you can do, really.

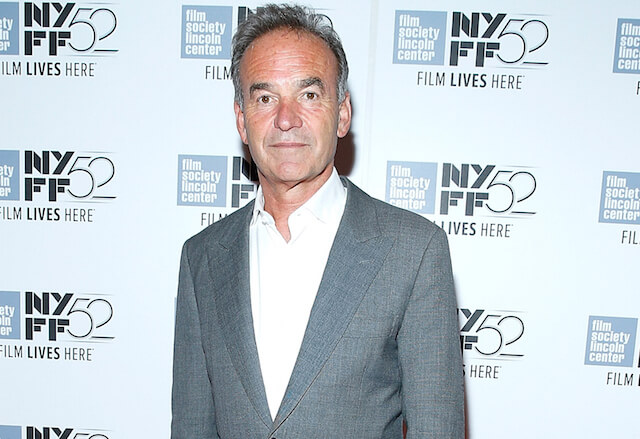

Interview: Nick Broomfield on the fun of making ‘Tales of the Grim Sleeper’

Getty Images

Follow Matt Prigge on Twitter @mattprigge