True crime has never felt quite so gripping.

The popularity of long, complex documentaries like “Making a Murderer” and “The Jinx,” and the radio podcast “Serial” are putting an immersive and realistic twist on TV crime staples and spurring heated debate about the shortcomings of the U.S. judicial system. And there is much more to come.

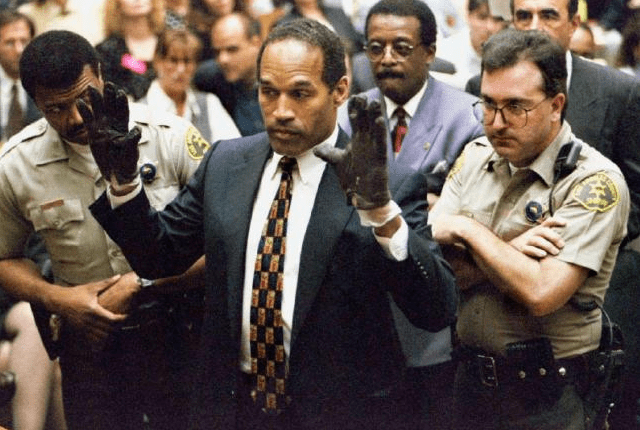

RELATED: Upcoming ‘Homeland’ season to be set, shot in NYC A much-anticipated, 10-episode TV series on the O.J. Simpson murder trial, which still fascinates and polarizes Americans 20 years on, will start on the FX channel in February. Discovery Channel last week began its six-episode “Killing Fields” series that takes viewers inside an active cold case murder investigation in Louisiana as it unfolds in real time. “What we’re seeing in this batch of shows is the idea that true crime can have some kind of social utility,” said David Schmid, an English professor at the State University of New York at Buffalo, and editor of the 2015 book “Violence in American Popular Culture.” “I think these shows are tapping into our culture’s widespread sense that our justice system, if not broken, is definitely in trouble,” Schmid added.

To be sure, police, crime and lawyers have been pop culture favorites for decades. But while TV franchises like “CSI” and “Law & Order” dramatize stories ripped from the headlines and package them into neat one-hour shows with star casts, what is grabbing American viewers now are hours-longseries portraying ordinary, imperfect people caught up in legal troubles that might never be fixed. “These shows let you go on a journey. It feels like audiences are solving it in real time, side-by-side with that hotshot investigator. You can be sitting on your couch in Oklahoma and you feel like you have solved a murder,” said Mark McBride, a Beverly Hills criminal defense attorney. McBride said the U.S. justice system often does not come out well in such series. Suggestions in the Netflix documentary series “Making a Murderer” that convicted Wisconsin scrap car dealer Steven Avery may have been framed by law enforcement for a 2005 murder have led hundreds of thousands of people to sign petitions calling for his pardon or a new trial. Authorities in the case have denied the allegations. Such concerns may be part of the fascination with the new breed of true crime shows. “People have had concerns about the justice system at least since the O.J. Simpson case in terms of evidence mishandling, biased detectives and lab technicians who are not superheroes,” said McBride. “I don’t think these (shows) undermine the system. I think the criminal justice system wants to be held accountable,” he said.

FX’s “The People vs. O.J. Simpson” limited series, which uses actors to dramatize the behind-the-scenes legal battle in the 1994 prosecution and murder trial of the football legend, has become one of the most buzzed-about TV shows weeks before its Feb. 2 launch even though it is not expected to throw any new light on the case. “The O.J. Simpson case brings together everything our culture is fascinated by —namely sex, sports, violence, celebrity and, in this case, race,” said Schmid.

However, Schmid noted that documentaries like “Serial” and “Making a Murderer” are a far cry from the lurid, melodramatic true crime narratives of past decades that seemed to celebrate killers. “What these shows have done is to take the alleged perpetrator and turned them into the victim,” Schmid added.

“Viewers get to feel that maybe, in a small way, they can contribute to making the justice system a little more responsive, a little more just. … That’s something which is relatively new in the history of the genre.”

What’s driving America’s obsession with true crime shows?

Reuters