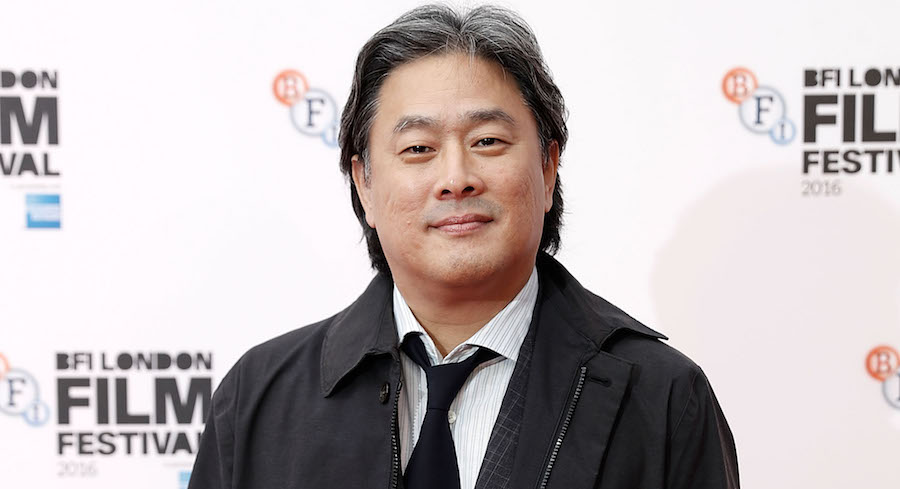

When the South Korean filmmaker Park Chan-wook does interviews, he doesn’t sit still. He walks around, sometimes staring at windows while rattling off answers. It’s due to a bad back, but it fits right in with his films, which are anything but staid. They’re overflowing with beautiful imagery, sneaky ideas and, usually, extreme yet comedic portrayals of violence. His latest, “The Handmaiden,” is in some ways a very different beast; its best scenes don’t involve extreme gore and unpleasant deaths, as in “Oldboy,” “Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance,” “Stoker” and “Thirst.” It adapts “Fingersmith,” Sarah Waters’ novel about two scheming women in Victorian England who fall in love mid-grift. Park relocates to 1930s Korea, during the Japanese colonization, and has turned in the most unabashedly romantic film he’s ever made — even if it’s still very Park. We talk to Park about working with female writers and his pitch that all of his grisly films are, deep down, love stories.

Tell me about moving the novel to this period in Korea. Would it have been much different if it had been set in Victorian England? I ask because I think “Stoker” feels very you, even though it’s an American film. RELATED: Interview: Gianfrano Rosi on “Fire at Sea,” the migrant crisis and filming death Your films always have romantic elements in them, but this is the rare one that’s ultimately a very passionate love story. Can you elaborate? I’d love to hear, for instance, how “Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance” is a love story. Even in “The Handmaiden,” though it’s a love story, its lovers spend much of the movie apart and suspect the other of betrayal. Especially considering “Thirst,” which is kind of an anti-love story, do you think you can only do love stories if they’re fraught with doubt? You worked with a female cowriter, Jeong Seo-Gyeong, on “Lady Vengeance,” “I’m a Cyborg, But That’s Okay” and “Thirst,” and you worked with another one, Chung Seo-kyung, on “The Handmaiden.” Was that a conscious decision, to make sure your female characters, who have either been the protagonists or co-protagonists, were fleshed out? Having a female cowriter on this does complicate any charges that come when a male filmmakers makes a film about lesbians, namely that it’s inevitable that it will succumb to the male gaze. There’s also a strong critique of the patriarchy. The movie is a gleeful takedown of these old men with old traditions, who oppress women and decide maybe the world would be best without men.

When I read “Fingersmith,” I had every intention of setting the story in Victorian England. It was only after my producer suggested the idea of setting it in the colonial era that my ears perked up, at the possibilities it opened up and the various elements I could add to the mix.

It’s very difficult to imagine what it would look like. It would be quite different from the BBC miniseries. And it would be very different from “The Handmaiden.”

It would be difficult to imagine what “Stoker” would have looked like if it had been a Korean film, just as it’s very difficult to imagine what the Victorian England of “The Handmaiden” would have looked like.

At Fantastic Fest in Austin, I heard they had these debates followed by a punch-out, where people argued for a given topic. The one they did this year was “Is ‘Rocky IV’ the greatest boxing movie of all time?” Hearing that, I suggested to them this topic: Prove that Park Chan-wook films are all fundamentally love stories. [Laughs] Because I think that’s true. If you reconsider all my films from that perspective, you might say, “He may have a point.”

There’s a relationship between the two kidnappers played by Shin Ha-kyun and Bae Doona. When her dead body is being transported by the elevator, he risks being caught and gets in the elevator with the police forensic team bringing her body down. And he surreptitiously holds her hand in a close-up. Some people say that’s a very romantic moment.

Of course. That’s what makes love great. [Laughs] With my wife, for instance, before marriage and even after marriage, I always think there’s peril lurking in the corner. If you’re not careful and if you don’t put effort into your relationship, you have no idea how quickly something might grow into a giant threat. [Beat] I feel like I’m giving a wedding speech: “Without sacrifice, without courage, without commitment to each other, love is difficult to maintain.” [Laughs]

You might think that, because of “Lady Vengeance,” I went looking for a female writer because I was writing a film with a female protagonist. But that wasn’t the case. Back then, the film I was thinking of was “Thirst.” I was just in search of a good writer, regardless if they were female or male. After I met [Jeong], I ended up changing the order around and making “Lady Vengeance” before “Thirst.” While working with her and putting a strong female protagonist at the center of my film, it made me really enjoy that process and made me more interested in telling stories with strong female characters.

That’s right. Although what happens when I work her is, because of the subject matter, I try to be more politically correct. I get crunched up. And she’s the one who says, “Come on, director Park, you’re trying mystify women too much. Woman can be like this.” [Laughs]

We would always joke around when writing the script that we would use this Japanese essay title called “Human Males We Don’t Need.” [Laughs]

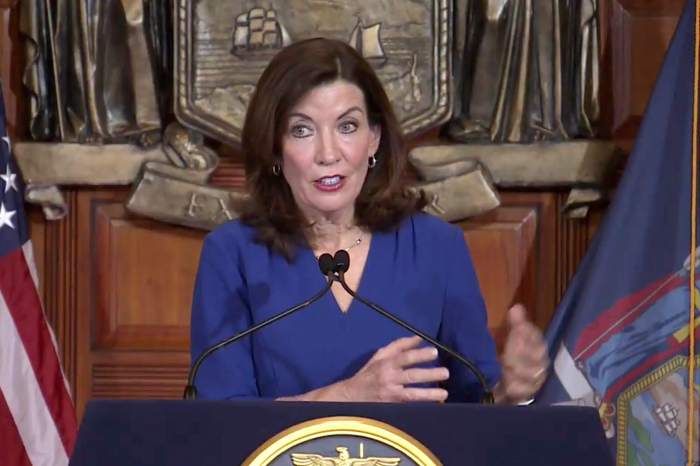

Park Chan-wook on ‘The Handmaiden’ and how all his films are love stories

Getty Images

Follow Matt Prigge on Twitter @mattprigge